What If Everyone Said No?

Why a US Trade Boycott Could Strengthen Global Business and Quality Standards

Trade disruptions can be unsettling, but they also create opportunities. If the world responded to US tariffs by excluding American trade and forming alternative alliances, the knee-jerk reaction would be fear of an economic downturn. However, history has shown that global markets adapt—sometimes for the better.

For Australian businesses, US trade isolation would undoubtedly cause short-term instability. Yet, in that disruption lies an opportunity to reassess supply chains,

diversify import sources, and secure better-quality goods at competitive prices. Many businesses have long relied on American products out of habit rather than necessity. A forced shift could uncover superior alternatives, strengthening the Australian economy in the long run.

We will examine the economic and business implications of a world moving forward without the US, focusing on quality control, trade resilience, and lessons from history.

The Tariff Fallacy: Short-Term Revenue, Long-Term Damage

Governments often justify tariffs to strengthen domestic industries and boost national revenue. The logic appears straightforward: governments can generate substantial income by imposing higher taxes on imported goods while encouraging local businesses to thrive. However, history and economic analysis suggest that this approach is flawed. Tariffs do not exist in a vacuum. They influence consumer behaviour, supply chains, international trade relationships, and economic conditions. When these factors are accounted for, it becomes clear that tariffs often fail to deliver the revenue and economic stability their proponents promise.

One of the most significant misconceptions surrounding tariffs is that they will increase government revenue in the long term. The assumption behind this belief is that import levels will remain constant even when tariffs rise, allowing the government to collect higher duties. However, this ignores fundamental economic principles.

Tariffs Do Not Always Generate More Revenue

Tariff revenue projections are often based on a static model that assumes businesses and consumers will continue to purchase imported goods at the same rate, simply absorbing the additional costs imposed by tariffs. Higher import duties alter purchasing behaviour in ways that can erode, rather than enhance, government revenue.

When tariffs increase, businesses and consumers respond in several predictable ways. Some seek alternative suppliers in countries with lower tariffs, reducing the volume of goods imported from tariffed nations. Others shift to domestically produced alternatives, even if they are more expensive or lower quality. In some cases, businesses and consumers cut back on spending altogether, reducing overall economic activity. Each of these reactions decreases the total amount of tariff revenue collected.

Historical examples reinforce this point. During the US-China trade war of 2018–2019, the United States imposed tariffs on hundreds of billions of dollars worth of Chinese imports. These measures were expected to generate billions in additional revenue while revitalising American manufacturing. Instead, importers sought alternative supply chains, often moving production to countries such as Vietnam, India, and Mexico. US businesses also absorbed much of the increased cost, which led to reduced profit margins, slower growth, and, ultimately, lower tax revenues from corporate earnings. By mid-2019, economic analyses found that the overall economic loss to the US far outweighed the revenue gained from tariffs.

Additionally, when tariffs make imported goods more expensive, they contribute to inflation, raising prices across the economy. Inflation reduces consumer spending power, lowering demand for imported and domestically produced goods. As consumption declines, businesses generate less revenue, leading to lower tax collections from income, corporate profits, and sales taxes. This creates a ripple effect where losses in other tax categories offset the supposed financial gains from tariffs.

Governments must also account for the cost of enforcement. Tariff regimes require administrative oversight, customs inspections, and legal mechanisms to prevent evasion as businesses seek ways to bypass tariffs—whether through reclassifying products, re-routing shipments, or using tax havens—governments are forced to allocate more resources to policing trade, further eroding any revenue gains.

Australia, like many open-market economies, recognises these risks. Its trade policies have historically prioritised free trade agreements that lower tariff barriers rather than raise them. The country’s experience shows that lower tariffs encourage economic expansion, increasing taxable revenue across multiple sectors rather than depending on import duties alone. This approach has allowed Australian businesses to thrive in a competitive global marketplace while maintaining stable economic growth.

The notion that tariffs will automatically generate more government revenue is, at best, an oversimplification and, at worst, a dangerous economic miscalculation. In reality, tariffs disrupt supply chains, reduce consumer spending, increase inflation, and trigger retaliatory measures from trading partners. In most cases, broader economic losses quickly overshadow the short-term tariff revenue boost. Rather than strengthening an economy, excessive tariffs risk isolating a nation from global trade networks, eroding business confidence, and undermining long-term economic prosperity.

Tariffs Increase Costs for Consumers and Businesses

The assumption that tariffs are a protective measure for domestic industries overlooks a critical economic reality: tariffs are an indirect tax on consumers and businesses. When a government imposes tariffs on imported goods, foreign producers do not bear the primary financial burden. Instead, the costs are transferred downstream—to businesses that rely on these imports and, ultimately, to the consumers who purchase the final products.

The mechanics of this cost transfer are straightforward. When import duties increase, businesses sourcing goods or raw materials from tariffed countries face higher procurement costs. To maintain profitability, they must either absorb these costs—reducing their margins and limiting reinvestment into growth—or pass them on to consumers through price increases. Either scenario results in economic inefficiencies. Reduced profitability stifles business expansion, hiring, and innovation, while increased consumer prices erode purchasing power, slowing overall economic activity.

A clear historical example of this dynamic was seen during the US-China trade war of 2018–2019. When the US government placed tariffs on Chinese imports, many American businesses paid significantly higher prices for essential goods, from electronics to industrial components. Some attempted to shift their supply chains to other countries, but this process was neither immediate nor cost-neutral. The transition required new supplier agreements, logistical adjustments, and regulatory compliance—all of which imposed additional costs. As a result, many businesses had no choice but to raise prices, affecting end consumers. Studies conducted during this period found that nearly 100% of the tariff costs were passed on to US consumers through higher prices.

Inflation is a natural consequence of this chain reaction. As tariffs push prices upward, the cost of living increases. Essential goods, including food, fuel, and household items, become more expensive. Businesses facing higher operating costs may demand wage increases to retain workers, but when inflation outpaces wage growth, real incomes decline, reducing disposable income and consumer spending. An economy reliant on consumer-driven growth creates a feedback loop of slowing demand, reduced business confidence, and weaker investment.

Small businesses are particularly vulnerable in such an environment. Smaller firms often have fewer alternatives than large corporations, which may have the resources to absorb short-term cost increases or relocate production. Many depend on fixed supply chains and lack the leverage to negotiate better terms with suppliers. If tariffs raise the price of essential goods—such as machinery, textiles, or technology components—small businesses either face a direct hit to their bottom line or are forced to increase prices, making them less competitive.

The Australian economy provides a valuable contrast. With a trade policy focused on free trade agreements and tariff reduction, Australia has kept import costs relatively low, ensuring that businesses and consumers benefit from competitive pricing. When Australian businesses can access lower-cost imports, they can invest more in productivity, innovation, and employment growth. By contrast, a tariff-heavy approach, such as the one proposed by the US, risks creating an artificial cost burden that restricts economic dynamism.

For consumers, the impact of tariffs extends beyond individual purchases. The broader economy slows as costs rise across multiple sectors, including retail, construction, and manufacturing. Interest rate policies may be adjusted in response to inflation, potentially leading to higher borrowing costs for businesses and households. This can dampen economic confidence, discourage investment, and result in an overall contraction of economic activity.

The notion that tariffs protect domestic industries is misleading when viewed through this broader economic lens. While some local producers may benefit from reduced foreign competition in the short term, the long-term impact of tariffs includes higher operating costs, inflationary pressure, reduced consumer spending, and weakened economic growth. History has shown that economies that embrace open trade policies tend to experience stronger, more sustainable expansion, while those that resort to protectionism often face economic stagnation.

Rather than shielding an economy, tariffs create an environment where businesses and consumers struggle with artificially inflated costs. In an interconnected global marketplace, no country operates in isolation. The costs imposed by tariffs ultimately extend beyond national borders, creating ripple effects that can hinder long-term economic stability and competitiveness.

Global Retaliation Weakens the US Economy

Trade is never a one-way street. When a country imposes import tariffs, its trading partners inevitably respond with countermeasures. Governments do not passively accept economic disadvantage; they retaliate by imposing tariffs, restricting market access, or forging alternative trade agreements that exclude the offending nation.

For the United States, the risk of such retaliation is particularly high. As one of the world’s largest economies, it relies heavily on imports and exports. While tariffs may be framed as a tool to reduce reliance on foreign goods, they also provoke immediate consequences—higher costs for domestic consumers and businesses, supply chain disruptions, and, critically, trade restrictions on US goods entering foreign markets.

The most immediate impact of retaliation is the erosion of export competitiveness. When US goods become subject to foreign tariffs, they become more expensive in international markets. This disadvantages American companies, as foreign consumers and businesses seek more affordable alternatives from other countries. Factors such as agriculture, automotive manufacturing, and technology are particularly vulnerable. If these sectors face reduced demand due to retaliatory tariffs, the economic fallout is not confined to corporations—it extends to workers, supply chains, and local economies reliant on these industries.

The US-China trade war of 2018–2019 offers a case study of how quickly retaliation can impact economic stability. When the United States imposed tariffs on Chinese goods, China responded in kind, targeting key American industries such as soybean exports, aviation, and semiconductors. The results were immediate: US farmers lost significant market share in China, with many struggling to find alternative buyers. Some had to destroy crops that could not be sold, while others relied on emergency government subsidies to offset their losses. Meanwhile, major corporations in sectors like automotive and electronics warned of declining global sales, citing retaliatory tariffs as a primary cause.

The long-term consequence of these trade wars is restructuring global supply chains. Businesses do not operate in uncertainty indefinitely; if a country becomes an unreliable trading partner, companies seek alternatives. This is particularly dangerous for the US, as competitors such as the European Union and China move aggressively to fill gaps left by American retreat. Once supply chains shift, they rarely revert. A foreign manufacturer that pivots from US suppliers to European or Japanese alternatives due to tariffs is unlikely to return to US-based sourcing once the trade war subsides. The loss of these relationships weakens the US’s global economic standing.

Additionally, global retaliation does not only take the form of direct tariffs. Trading partners can impose regulatory barriers, increase scrutiny on US imports, or delay approvals for American companies seeking to expand internationally. Even beyond formal restrictions, trade wars foster an adversarial climate, making cooperation on global economic and security issues more difficult. Nations that feel economically sidelined by US policies may also form strategic alliances that diminish American influence, particularly in regions such as the Asia-Pacific and Latin America, where trade relationships are crucial in diplomatic engagement.

From a geopolitical standpoint, aggressive tariff policies risk accelerating the rise of competing economic blocs. China has capitalised on US protectionism by positioning itself as a champion of global trade, leading initiatives such as the Belt and Road Initiative and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). The European Union has also expanded its network of trade agreements, securing deals with Canada, Japan, and other major economies. If the US isolates itself through protectionist policies, it risks sidelining its industries, allowing its competitors to dictate the future of global trade.

For small businesses in the United States, the impact of global retaliation is particularly acute. Many rely on exports as a core component of their revenue streams, and even minor tariff increases can mean the difference between profitability and financial distress. Unlike multinational corporations, which can adjust supply chains and absorb short-term losses, small businesses often lack the resources to navigate sudden trade restrictions. As a result, they face greater risk of closure, job losses, and long-term market exclusion.

Historically, economies that have embraced open trade policies have demonstrated stronger long-term growth than those that have relied on protectionist measures. The economic success of countries such as Germany, Singapore, and Australia has been built on trade diversification rather than reliance on restrictive tariffs. When nations engage openly in global commerce, they benefit from competitive pricing, technological exchange, and access to a broader consumer base. In contrast, economies that have pursued isolationist policies—such as Argentina’s periods of trade protectionism in the late 20th century—have often experienced economic stagnation and declining global influence.

The idea that tariffs strengthen an economy by shielding it from competition is rooted in short-term thinking. In reality, they invite retaliation, reduce export competitiveness, and accelerate the decline of industries dependent on global markets. For the United States, the risks of global retaliation are not just economic—they are strategic. If the world moves forward without the US in major trade agreements, the country’s economic and geopolitical standing will erode, leaving American businesses and consumers with fewer choices, higher costs, and weaker international influence.

Forced Supply Chain Reviews: A Blessing in Disguise?

If global markets moved away from US trade, businesses would be forced to review their supply chains, which often reveals surprising benefits.

The Myth of US Quality Superiority

The perception that American-made products are inherently superior to those from other nations has been ingrained in global trade for decades. While the United States has produced some of the world’s most recognised brands and innovations, this reputation does not always align with present-day reality. A forced review of global supply chains, prompted by US trade isolation, may lead businesses to discover that many non-US manufacturers offer products of equal or higher quality at competitive prices.

Historically, American manufacturing set global benchmarks in the automotive, aerospace, and technology industries. However, the assumption that US goods are always the best choice is increasingly outdated. In many industries, other nations have caught up and sometimes surpassed US production standards. The automotive sector provides a clear example. While US automakers were once dominant, companies from Germany, Japan, and South Korea have earned stronger reputations for reliability, innovation, and efficiency. Brands such as Toyota, BMW, and Hyundai consistently outperform their US counterparts in international rankings for quality and durability.

Electronics and precision manufacturing tell a similar story. While Silicon Valley remains a hub for technological innovation, much of the production and assembly of electronic components occurs in Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan. Companies such as TSMC, Samsung, and Sony have become industry leaders in semiconductor manufacturing, optics, and consumer electronics—fields where the US has struggled to compete at the same level of precision and efficiency. Even in sectors like pharmaceuticals and medical technology, European firms often set higher standards for research, regulation, and production consistency than their American counterparts.

A reliance on US imports has, for many businesses, been driven more by habit than necessity. Companies sometimes continue to source from the US simply because existing contracts, supplier relationships, and logistics networks make it the default option. However, a closer examination of the global market reveals a wealth of alternatives that may offer better quality, greater reliability, or improved value for money.

When trade barriers force companies to reconsider their sourcing strategies, they often uncover better options. Countries such as Germany and Switzerland are renowned for their engineering and precision manufacturing, producing industrial components, machinery, and medical equipment that are often superior to their US equivalents. Japan and South Korea lead in high-tech industries, offering advanced consumer electronics and semiconductor technology that outpace many American brands. Even within the Asia-Pacific region, countries such as Australia, Singapore, and Taiwan have rapidly developed high-quality manufacturing capabilities that meet or exceed US standards.

For Australian businesses, the opportunity to diversify suppliers away from the US could lead to improved product quality and cost efficiency. Many Australian firms have benefited from trade agreements granting them access to high-standard goods from Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. As US trade policies become more unpredictable, shifting towards alternative suppliers can provide greater stability and long-term value.

A forced review of supply chains, while disruptive in the short term, ultimately serves as a competitive advantage for businesses willing to embrace change. By breaking away from outdated assumptions about US quality superiority, companies can find suppliers that offer better products, improved reliability, and cost-effective alternatives. In the long run, a diversified sourcing strategy strengthens resilience, reduces dependency on any single nation, and ensures that businesses remain agile in an evolving global marketplace.

Competitive Pricing from Alternative Markets

One of the strongest arguments against over-reliance on US imports is the assumption that they offer the best value for money. While some American products maintain high standards, the global market has evolved significantly, offering businesses access to comparable or superior alternatives at more competitive prices. If the rest of the world responded to US trade isolation by restructuring supply chains, companies would be forced to reconsider their procurement strategies—often leading to improved cost efficiency and better financial outcomes.

The notion that US-made goods are universally cost-effective ignores the reality of global manufacturing dynamics. Many industries have moved their production bases to regions with lower labour costs, advanced manufacturing capabilities, and streamlined logistics networks. Countries such as Germany, South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan have not only matched but, in many cases, exceeded US standards in critical sectors while maintaining pricing that is either on par with or lower than American alternatives.

Take the electronics industry, for example. While the United States remains a hub for software development and technological innovation, much of the hardware production has already shifted to Asia. Companies such as Taiwan’s TSMC, South Korea’s Samsung, and Japan’s Sony dominate semiconductor and consumer electronics manufacturing. These firms offer cutting-edge technology and operate within highly efficient supply chains that allow them to produce high-quality components at lower costs than US-based manufacturers. Businesses that rely on US tech imports may find that sourcing directly from Asian manufacturers reduces expenses while maintaining or improving product quality.

Automotive manufacturing presents another case study. While the US remains a key player in vehicle production, global car manufacturers from Germany, Japan, and South Korea often outperform American brands regarding quality, reliability, and cost-effectiveness. Australian businesses in the automotive parts, logistics, and transportation sectors have long benefited from trade relationships with these countries, and a forced shift away from US imports could further enhance these ties, ensuring access to premium products at competitive prices.

The pharmaceutical and healthcare sectors also illustrate the advantages of trade diversification. Many of the world’s most advanced medical research facilities and pharmaceutical manufacturers are in Europe, notably Switzerland, Germany, and the United Kingdom. With strict regulatory standards and highly efficient production systems, these countries produce medicines, medical devices, and healthcare technologies that often surpass US benchmarks. Businesses reliant on American healthcare imports could find that European alternatives offer superior quality and cost savings.

Reducing dependence on US imports can provide substantial financial benefits for Australian small businesses. As the country strengthens its trade agreements within the Asia-Pacific region, firms have increasing access to high-quality products from countries that operate under lower production costs while maintaining strong regulatory standards. The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) have already provided Australian businesses with expanded trade opportunities. Australia’s existing and emerging partnerships could offer greater advantages if the US is excluded from global trade alliances.

The cost savings from sourcing alternatives extend beyond just direct pricing. Reduced tariffs, lower shipping costs, and streamlined customs processes in free trade agreements can make non-US imports significantly attractive. Businesses that proactively explore alternative suppliers will be better positioned to absorb economic shifts and maintain competitive consumer pricing.

A supply chain review may initially seem like an administrative burden, but history has shown that businesses willing to adapt often emerge stronger. In response to the US-China trade war, the trade realignments demonstrated how companies that diversified their supply chains mitigated financial risks and found new growth opportunities. Businesses that once depended on China pivoted to Vietnam, India, and Mexico, discovering cost advantages and operational efficiencies. A similar shift away from US imports could lead Australian businesses to find better pricing, higher quality, and more reliable trade relationships elsewhere in the global economy.

Ultimately, the idea that US imports are always the most cost-effective option is outdated. The global economy offers an increasing number of viable alternatives, many of which provide superior quality at a lower price point. A forced supply chain review presents an opportunity, not a setback. Businesses embracing diversification and seeking competitive pricing in alternative markets will be more resilient, profitable, and better positioned for long-term success.

The Resilience Factor

A diversified supply chain is a business’s most effective risk management strategy. Relying too heavily on a single country—particularly one as politically and economically volatile as the United States—creates vulnerabilities that can quickly become liabilities. The unpredictability of US trade policies and the risk of tariff escalations and economic isolation highlight why businesses must take a more strategic approach to sourcing. A forced review of supply chains due to US trade isolation would ultimately strengthen global business resilience, ensuring greater stability and flexibility in an increasingly uncertain economic landscape.

Resilient supply chains are built on diversification. When businesses source from multiple countries rather than concentrating their imports in one region, they mitigate the risks associated with economic disruptions, political instability, and logistical bottlenecks. The COVID-19 pandemic showed how over-reliance on a single country for essential goods can lead to severe consequences. Many businesses that depended on China for raw materials and manufacturing faced crippling shortages when supply chains were disrupted. Those who had diversified their supplier networks could adjust more quickly and maintain operations with fewer setbacks.

The same principle applies to US imports. If Australian businesses continue to rely disproportionately on American goods, they expose themselves to unnecessary economic risk. A trade war, an unexpected regulatory shift, or political instability in the US could create immediate disruptions. Businesses that have already established alternative supply chains in Europe, Asia, and other markets will be far better positioned to navigate such changes with minimal impact.

Another key factor in supply chain resilience is cost stability. US trade isolation leads to price volatility, with businesses facing sudden cost increases on essential goods due to tariffs and shifting economic policies. Companies that rely exclusively on US imports would be at the mercy of these fluctuations, unable to predict or control their long-term procurement costs. By diversifying suppliers, businesses can take advantage of stable pricing structures in other regions, reducing their exposure to sudden economic shocks.

Technological advancements have made supply chain diversification more accessible than ever. Digital procurement platforms, global logistics networks, and trade agreements such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) have made it easier for businesses to identify, vet, and engage with alternative suppliers. Businesses that embrace these opportunities will reduce their dependence on US imports and enhance their long-term competitive advantage.

For small businesses, resilience is particularly critical. Unlike large multinational corporations that can absorb short-term losses and negotiate favourable terms with suppliers, small businesses often operate with tighter margins and less financial flexibility. A sudden price hike or supply chain disruption can have devastating consequences. By proactively seeking alternative suppliers and reducing reliance on US goods, small businesses can insulate themselves from global economic shifts and maintain operational stability.

There is also a strategic advantage in aligning with emerging markets. As the global economy continues evolving, nations such as Vietnam, India, and South Korea rapidly expand their manufacturing and export capabilities. Businesses establishing relationships with these markets early will benefit from lower costs, better trade terms, and a more dynamic supply chain. This forward-thinking approach ensures businesses remain competitive, agile, and prepared for future economic transformations.

The shift away from US dependency is not just a defensive measure but an opportunity to build a more adaptable, cost-effective, and robust supply chain. Companies that take proactive steps to diversify their sourcing strategies will emerge as industry leaders, ready to navigate an increasingly complex global trade environment. The resilience gained through diversification is a safeguard against economic uncertainty and a foundation for long-term success and sustainable growth.

Lessons from History: Crisis as a Catalyst for Change

Trade isolation is not a new phenomenon. Economic history provides key lessons in how economies respond to significant shifts.

The Great Depression and Protectionism

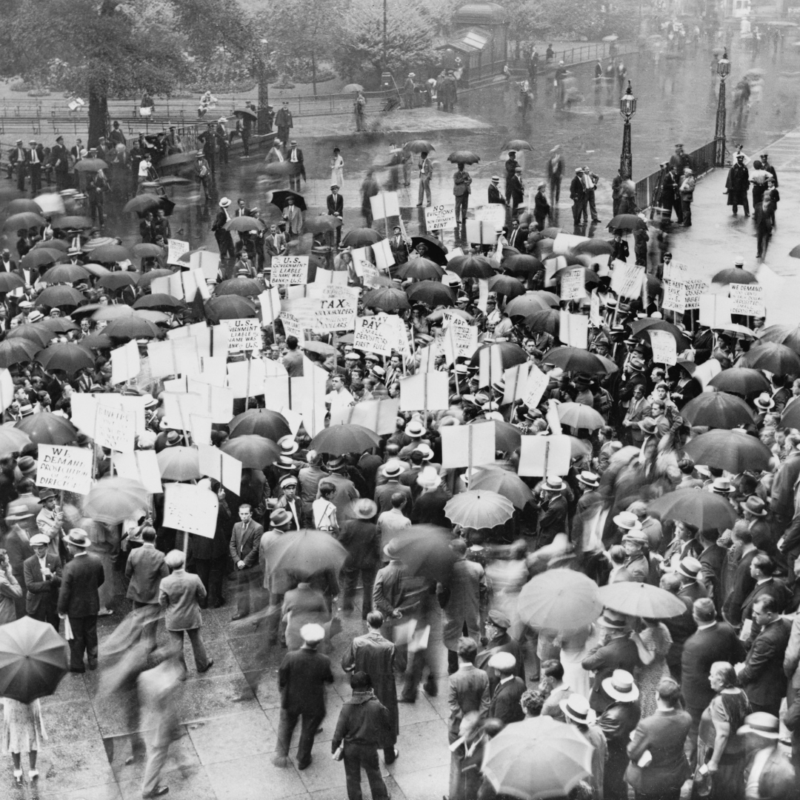

History has repeatedly shown that economic protectionism, particularly when driven by high tariffs, often leads to unintended consequences that exacerbate financial downturns rather than alleviating them. One of the most striking examples occurred during the Great Depression when the United States introduced the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, a policy intended to protect American industries from foreign competition. Instead of reviving the economy, these aggressive tariff measures triggered a wave of global retaliation, deepening the economic crisis and prolonging financial hardship.

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff was designed to shield American businesses and workers by imposing steep duties on more than 20,000 imported goods. The expectation was that by making foreign products more expensive, American consumers and businesses would turn to domestically produced alternatives, thereby boosting internal economic activity. However, this assumption failed to account for the global nature of trade and the inevitable response from other nations.

In reaction to these tariffs, major US trading partners—including Canada, Britain, France, and Germany—retaliated with their tariff increases, effectively shutting American goods out of key international markets. As a result, US exports plummeted by more than 60% between 1929 and 1933, devastating industries that relied on foreign buyers. American farmers were among the most brutal hit, as agricultural exports collapsed, leaving surplus crops to rot while domestic demand remained insufficient to absorb production. The supposed benefits of protectionism quickly evaporated as businesses faced declining revenues, job losses surged, and economic conditions worsened.

The global economy suffered in tandem. As countries implemented protectionist policies in response to US tariffs, international trade shrank dramatically. The flow of goods between nations slowed, deepening the economic malaise and causing widespread business closures and unemployment. This period of economic contraction not only worsened the Great Depression but also set the stage for long-term shifts in global economic policies.

A critical lesson from this era is that economic isolation rarely leads to prosperity. While tariffs may provide short-term relief for select industries, they create broader disruptions that often outweigh any initial gains. The protectionist policies of the 1930s demonstrated that when one nation attempts to shield itself from competition through high tariffs, others will respond in kind, leading to a breakdown in global trade cooperation.

The mistakes of the Great Depression eventually gave rise to a more open and cooperative global economic framework. Following World War II, nations recognised the dangers of extreme protectionism. They worked to establish trade institutions such as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which later evolved into the World Trade Organization (WTO). These agreements helped stabilise international trade and prevent the kind of retaliatory tariff wars that had proven so damaging in the 1930s.

For modern economies, the lessons of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff remain highly relevant. Any attempt to isolate an economy through high tariffs risks triggering reciprocal actions that harm domestic and international markets. The world is more interconnected than ever, and trade restrictions on one end create ripple effects that impact industries, businesses, and consumers on a global scale.

US trade isolation through heavy tariffs could lead to similar economic disruptions in the current landscape, particularly for export-dependent sectors. Nations that rely on trade with the United States may seek alternative partnerships, forming stronger economic alliances elsewhere and leaving the US with reduced influence in global commerce. The historical precedent set by the Great Depression serves as a clear warning: protectionism does not create economic security; it often deepens financial instability and drives nations further into economic hardship.

The key takeaway from this historical episode is that economies thrive when they remain open, diversified, and engaged with global markets. The collapse of trade during the Great Depression proved that prosperity was not achieved through isolation but through strategic collaboration and the facilitation of cross-border commerce. As global markets evolve, businesses and policymakers must recognise that short-term protectionist measures often lead to long-term economic setbacks. The resilience of an economy depends not on its ability to shut out competition but on its capacity to adapt, innovate, and participate fully in the global trading system.

The Oil Crisis of the 1970s

The oil crisis of the 1970s was one of the most significant economic shocks of the modern era, reshaping global trade, energy policies, and economic resilience. Unlike previous crises that were driven by financial mismanagement or market instability, the oil crisis was primarily geopolitical, triggered by a shift in global power dynamics and economic leverage. The crisis demonstrated the vulnerabilities of over-reliance on a single supply source and provided critical lessons on diversification, strategic planning, and long-term economic adaptation.

The crisis began in October 1973, when the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC), led by major oil producers such as Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, imposed an oil embargo against nations that supported Israel during the Yom Kippur War, including the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and several Western European countries. The embargo was designed as an economic weapon, restricting oil exports and increasing prices. The effects were immediate and severe. The cost of oil quadrupled, rising from $3 per barrel to nearly $12 per barrel within a few months, sending shockwaves through global economies.

The consequences were devastating for oil-dependent nations, particularly those in the West. The sudden spike in energy costs led to inflation, stagnation, and recession, a combination that came to be known as stagflation. In this phenomenon, stagnant economic growth occurs alongside rising inflation. Businesses struggled to cope with soaring fuel costs, while consumers faced dramatic increases in the price of petrol, electricity, and everyday goods. Long queues at petrol stations became common, and governments were forced to implement fuel rationing and emergency economic measures.

Yet, despite the immediate turmoil, the crisis served as a powerful catalyst for change. The shock forced governments and businesses to reassess their dependency on a single region for critical resources, leading to widespread energy diversification efforts. Countries that had long relied on Middle Eastern oil began investing in alternative energy sources, expanding domestic production, and forging new trade relationships to reduce vulnerability to future supply shocks.

One of the most significant responses was the establishment of strategic petroleum reserves. The United States created the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) in 1975, ensuring that stored oil reserves could mitigate future supply disruptions. Similarly, other nations implemented stockpiling strategies and encouraged more significant energy conservation to reduce immediate reliance on volatile oil markets.

The crisis also accelerated the global shift towards nuclear power, natural gas, and renewable energy. Many countries recognise the dangers of over-reliance on a single energy source and have increased investment in nuclear power plants and hydroelectric infrastructure. In Japan and France, nuclear energy became a dominant part of the national energy strategy, reducing dependence on imported oil. The crisis also laid the foundation for modern renewable energy policies, as nations began exploring solar and wind power as long-term solutions to energy security concerns.

The automotive industry underwent significant transformation as well. The sharp increase in fuel prices led to a decline in demand for large, fuel-inefficient vehicles, prompting innovation in fuel economy standards. Japan’s automotive sector, particularly companies such as Toyota and Honda, capitalised on this shift by producing smaller, more fuel-efficient vehicles that quickly gained market dominance in the US and Europe. This period marked the rise of Japanese automakers as global industry leaders, challenging the dominance of American car manufacturers that had been slow to adapt to changing consumer preferences.

The oil crisis also triggered a fundamental change in global trade relationships. Western nations sought to reduce their dependence on OPEC-controlled oil, leading to increased exploration and production in regions such as the North Sea (UK and Norway), Alaska, and Canada. This diversification helped stabilise global oil markets over time and reduced the ability of any single group of nations to wield absolute control over energy supplies.

From a geopolitical standpoint, the oil crisis reinforced that economic power is deeply tied to resource control. Nations that can manipulate supply chains—whether in energy, technology, or raw materials—can exert substantial influence over global markets. The events of the 1970s demonstrated that reliance on a single dominant supplier is a vulnerability, not a strength and that economic resilience depends on diversification, strategic planning, and long-term investment in alternatives.

For modern businesses and policymakers, the lessons of the oil crisis remain highly relevant. Whether in energy, technology, or manufacturing, supply chain dependency creates risks that can be exploited in geopolitical tension. Just as the 1970s crisis prompted a shift towards energy diversification, today’s global economic environment requires businesses to rethink their reliance on any one nation—such as the United States—for critical imports and supply chains; the most successful economies are those that adapt, diversify, and position themselves for long-term stability, rather than clinging to outdated dependencies that leave them vulnerable to sudden disruptions.

In hindsight, the oil crisis of the 1970s was not just a period of economic hardship—it was a turning point that reshaped global trade and energy policy for decades to come. The nations and businesses that adapted to the challenges emerged stronger, more resilient, and better prepared for future economic shifts. Today, as global supply chains undergo their transformations, the lessons from this crisis serve as a crucial reminder that adaptability and strategic diversification are the foundations of long-term economic security.

The 2018–2019 US-China Trade War

The 2018–2019 US-China trade war is a contemporary example of how protectionist policies can disrupt global supply chains, alter trade dynamics, and drive businesses to reconsider long-standing assumptions about market stability. The conflict began when the United States, under the Trump administration, imposed a series of tariffs on Chinese imports to reduce the US trade deficit and address concerns over intellectual property theft and forced technology transfers. In response, China retaliated with its tariffs on American goods, sparking a tit-for-tat escalation that significantly impacted economies and global trade.

The trade war had several immediate economic consequences. For the United States, tariffs on Chinese imports resulted in higher costs for businesses and consumers. Companies reliant on Chinese manufacturing faced increased expenses as components, raw materials, and finished goods rose sharply. This led to inflationary pressures within the US market, affecting the electronics and agriculture sectors. American consumers ultimately bore the brunt of these price increases as businesses passed on the additional costs.

The agricultural industry was particularly hard hit. China, one of the largest importers of US soybeans, pork, and other agricultural products, responded by imposing high tariffs on these goods and shifting its purchases to alternative suppliers like Brazil and Argentina. The resulting decline in demand left American farmers with unsold stockpiles, leading to financial distress and reliance on government subsidies to offset losses. The shift in Chinese sourcing patterns highlighted how quickly market dynamics can change in response to trade conflicts, causing long-term damage to previously stable trade relationships.

From China’s perspective, the tariffs disrupted its manufacturing sector, particularly in industries where the US was a major customer. However, the Chinese government implemented measures to stabilise its economy, including monetary easing and increased support for domestic businesses. Moreover, the trade war accelerated China’s efforts to diversify its export markets, strengthening ties with Europe, Asia, and emerging economies. This strategic shift reduced China’s dependence on the US market and positioned it for greater resilience in the face of future trade tensions.

The broader impact of the trade war was felt throughout the global economy. Businesses in other countries that relied on US-China trade flows faced uncertainty and increased costs due to the disruption of supply chains. Multinational corporations with complex global supply networks were forced to reconsider their sourcing strategies, seeking alternative manufacturing bases in countries such as Vietnam, India, and Mexico. This shift in supply chains demonstrated the vulnerability of over-reliance on any single market and underscored the importance of diversification.

A notable outcome of the trade war was accelerating the “China plus one” strategy, where companies maintained production in China but also established manufacturing operations in another country to mitigate risk. This approach aimed to balance cost efficiency with geopolitical stability, ensuring businesses could adapt quickly to future disruptions. The trend towards diversification also opened new opportunities for Southeast Asian countries, which benefited from increased foreign investment as companies sought to reduce their exposure to the US-China trade conflict.

For the technology sector, the trade war had profound implications. The US imposed export restrictions on Chinese tech giant Huawei, limiting its access to critical components and software. In response, China increased investment in its domestic semiconductor industry, aiming to reduce its reliance on US technology. This shift highlighted the risks associated with global tech dependencies and prompted a push for greater self-sufficiency in key areas of innovation and manufacturing.

The financial markets reflected the uncertainty caused by the trade war, with increased volatility as investors reacted to new tariff announcements and shifting economic forecasts. While some US companies were able to adjust their supply chains, others experienced significant profit declines and reduced market competitiveness. The uncertainty also affected business confidence, delaying investment decisions and slowing economic growth in both the US and China.

Despite the adverse short-term effects, the US-China trade war provided valuable lessons for businesses and policymakers. It underscored the importance of supply chain resilience, highlighting the need to avoid over-dependence on a single country or region. Companies that had already diversified their sourcing strategies were better equipped to navigate the disruptions, demonstrating the advantages of flexibility in global operations.

Furthermore, the trade war revealed the limitations of aggressive protectionist policies in a highly interconnected global economy. While tariffs were intended to protect domestic industries and reduce trade deficits, they often resulted in higher consumer costs and retaliatory measures that harmed exporters. The long-term impact of the trade war suggested that collaborative approaches to trade disputes, rather than unilateral tariffs, are more effective in maintaining economic stability and fostering growth.

For Australia, the trade war between the US and China highlighted the importance of maintaining balanced trade relationships and diversifying export markets. As an economy heavily reliant on trade with China, Australia faced potential vulnerabilities if geopolitical tensions escalated further. However, the crisis also presented opportunities to strengthen ties with other Asian nations and explore new markets in Europe and North America.

The 2018–2019 US-China trade war demonstrated that economic crises often drive necessary adaptations and strategic shifts. Businesses that proactively diversified their supply chains embraced innovation and maintained a global outlook that emerged stronger and more resilient. The lessons from this period emphasise that while protectionist measures may offer short-term political gains, the long-term health of the global economy depends on open, stable, and diversified trade relationships.

Strategic Implications for Australia

A world without US trade dominance presents challenges and unique opportunities for Australia.

Strengthening Trade Ties with Asia-Pacific

As the global trade landscape shifts, Australia finds itself in a unique position to strengthen its economic partnerships within the Asia-Pacific region. The ongoing trend of trade diversification, exacerbated by geopolitical tensions and protectionist policies in the United States, has accelerated the need for Australia to solidify its role as a key player in regional trade agreements. Strengthening economic ties with Asia-Pacific nations is a strategic necessity and a long-term opportunity to ensure stability, economic resilience, and continued growth.

Australia has long benefited from strong trade relationships with Asia, with key export markets including China, Japan, South Korea, and members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). These markets have become increasingly important as global trade flows shift from traditional Western-centric models to a more regionally integrated approach. As the US pursues policies that could isolate it from international trade agreements, Australia has a clear incentive to deepen its ties with Asian economies, ensuring it remains at the forefront of regional economic integration.

The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) has been instrumental in Australia’s strategy for trade diversification. This multilateral trade agreement, which includes major economies such as Japan, Canada, and Mexico, provides Australian businesses preferential access to high-growth markets while reducing tariff barriers. By expanding economic cooperation within this framework, Australia can mitigate risks associated with reliance on any single trading partner, particularly in light of the US’s uncertain trade policies.

Another crucial agreement is the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), the world’s largest free trade pact, which includes ASEAN nations, China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand. The RCEP enhances market access and simplifies trade regulations, creating new opportunities for Australian exporters across various industries, from agriculture and mining to education and professional services. By capitalising on the advantages offered by this agreement, Australian businesses can secure long-term access to dynamic and rapidly expanding consumer markets.

China remains Australia’s largest trading partner, and while diplomatic tensions have occasionally strained economic relations, trade between the two nations has remained resilient. China’s demand for Australian resources, particularly iron ore and natural gas, has been a cornerstone of Australia’s economic stability. However, recent developments have underscored the importance of diversifying trade within Asia. Expanding trade with Japan, South Korea, and India can provide greater balance, reducing vulnerability to potential economic coercion or disruptions from any single partner.

India, in particular, presents a significant opportunity for Australia’s trade future. As one of the fastest-growing major economies, India offers vast potential for Australian education, technology, and energy exports. The Australia-India Economic Cooperation and Trade Agreement (AI-ECTA), signed in 2022, has laid the groundwork for enhanced trade relations, lowering tariffs on Australian goods and opening new channels for investment and collaboration. Strengthening this relationship could position Australia as a key partner in India’s economic transformation, providing long-term benefits for Australian businesses.

The ASEAN bloc also represents a critical market for Australian trade. With a combined population exceeding 660 million and a rapidly growing middle class, ASEAN countries offer significant opportunities for Australian exports, particularly in agri-business, education, and infrastructure development. Strengthening partnerships with nations such as Vietnam, Indonesia, and Malaysia could further enhance Australia’s economic resilience, reducing reliance on Western markets and fostering greater regional stability.

Beyond traditional goods exports, Australia has a substantial opportunity to expand its trade in services, particularly in finance, education, and technology. As Asia’s economies modernise, the demand for high-quality education and professional expertise is rising. Australia’s world-class universities and skilled workforce are in a strong position to meet this demand, further integrating the country into Asia’s economic growth trajectory.

In the wake of shifting global trade alliances, Australia’s strategy should focus on securing long-term economic partnerships within the Asia-Pacific. By leveraging its involvement in trade agreements such as CPTPP and RCEP, diversifying export markets, and strengthening relationships with emerging economies such as India and ASEAN, Australia can build a trade framework that is less reliant on Western markets and more aligned with the realities of modern global commerce. The long-term benefits of this approach will provide economic stability and reinforce Australia’s position as a key player in the Asia-Pacific, ensuring continued prosperity in an era of evolving trade dynamics.

Expanding Domestic Manufacturing

The increasing volatility of global trade, driven by shifting economic alliances and geopolitical tensions, gives Australia an opportunity to reassess its industrial strategy. Expanding domestic manufacturing is not simply a reaction to trade disruptions but a strategic move towards greater economic resilience, job creation, and technological advancement. As the global economy undergoes realignment, Australia has the chance to strengthen its industrial base, reducing dependence on imports and securing critical supply chains.

For much of the 20th century, manufacturing played a central role in Australia’s economy. However, the rise of globalisation and lower-cost international production led to a steady decline in local manufacturing industries. The closure of Australia’s automotive industry and the offshoring of key production sectors demonstrated the risks of relying too heavily on foreign supply chains. Recent trade disruptions, including the US-China trade war and pandemic-related supply shortages, have highlighted the importance of strong domestic manufacturing capability.

Strengthening local manufacturing offers several strategic benefits. Firstly, it enhances supply chain security by ensuring that essential industries—such as healthcare, defence, and energy—are not vulnerable to external market fluctuations. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed weaknesses in supply chains, with shortages of medical equipment, pharmaceuticals, and essential goods highlighting Australia’s reliance on foreign production. By increasing domestic production capacity, the country can insulate itself from future disruptions and ensure that critical supplies remain available during times of crisis.

Secondly, manufacturing expansion supports economic diversification. While Australia’s mining and resources sector remains a key pillar of the economy, long-term stability requires a more balanced industrial base. Investing in high-value manufacturing, such as renewable energy technology, advanced engineering, and medical research, can help reduce dependence on commodity exports and create more sustainable economic growth.

Technological innovation will play a crucial role in making Australian manufacturing globally competitive. Advanced manufacturing techniques, including automation, artificial intelligence, and additive manufacturing (3D printing), can improve efficiency, lower costs, and increase production capacity. By integrating these technologies, Australian manufacturers can compete with international producers while maintaining high-quality standards.

Government policy and investment will be essential in facilitating this shift. Initiatives such as the Modern Manufacturing Strategy, designed to boost Australia’s sovereign capability in key industries, provide financial support and incentives for local production. Expanding these policies and increasing research and development funding will help Australian manufacturers scale their operations and enhance their competitiveness in global markets.

One sector with significant potential is renewable energy manufacturing. Demand for solar panels, battery storage systems, and hydrogen technology is increasing as the world transitions towards sustainable energy solutions. Australia, with its abundant natural resources and expertise in energy production, is well-positioned to become a leader in renewable energy manufacturing. Investing in domestic production within this sector can create jobs, strengthen local industry, and provide new export opportunities to markets seeking clean energy solutions.

Developing a skilled workforce is another critical factor in expanding domestic manufacturing. Upskilling workers in advanced manufacturing processes, automation, and engineering will be necessary to support industry growth. Stronger partnerships between universities, technical institutions, and industry leaders can ensure that the workforce is equipped to meet the demands of a modernised manufacturing sector.

Australia’s existing free trade agreements, including the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), offer pathways for Australian-made products to access international markets. By leveraging these agreements, Australian manufacturers can integrate into regional supply chains, increasing global competitiveness.

Expanding domestic manufacturing is not about reversing globalisation but about ensuring strategic self-sufficiency. A stronger manufacturing sector will reduce reliance on imports in critical areas while positioning Australian-made products as competitive exports. With the right investments, policies, and technological advancements, Australia can transform its industrial base into a key economic stability and long-term prosperity driver.

A Stronger Australian Dollar?

The potential shift in global trade dynamics, particularly in response to US trade isolation, could have significant implications for currency markets, including the strength of the Australian dollar. Economic performance, trade balances, commodity prices, and investor confidence influence exchange rates. If the US economy experiences contraction due to restricted trade access, this could lead to shifts in capital flows, potentially strengthening the Australian dollar relative to the US dollar.

One of the primary factors influencing the value of the Australian dollar is commodity exports. Australia is one of the world’s largest exporters of iron ore, coal, and liquefied natural gas (LNG), and the demand for these resources directly impacts the exchange rate. If global trade realigns in a way that increases demand for Australian commodities—particularly from Asia-Pacific partners—this could result in a rise in the Australian dollar. Additionally, as nations move away from reliance on US imports, increased trade activity between Australia and emerging markets could further bolster demand for the currency.

Investor sentiment also plays a key role in currency valuation. If global markets perceive the US economy as weakened by protectionist policies, investment capital could shift to more stable, trade-friendly economies. With its strong banking sector, stable political environment, and well-established trade agreements, Australia may be considered a safer destination for foreign direct investment and capital inflows. An increase in foreign investment would further support the Australian dollar, particularly if global funds seek alternatives to US-dollar-denominated assets.

Trade surpluses and deficits also contribute to currency fluctuations. With its persistent trade deficit, the US may see downward pressure on the US dollar if exports decline due to retaliatory tariffs and reduced global market access. In contrast, Australia, which has maintained a strong trade surplus due to high commodity exports, could see an appreciation of its currency as global trade patterns shift in its favour. If alternative trade agreements result in stronger demand for Australian exports, this could place upward pressure on the Australian dollar.

However, a stronger Australian dollar is not without its challenges. While an appreciating currency benefits importers by making foreign goods and services cheaper, it can also create difficulties for exporters by making Australian products more expensive on the global market. Industries such as tourism, education, and agriculture, which rely on competitive pricing in international markets, may face headwinds if the dollar rises too sharply. Balancing a strong currency and a competitive export sector will require careful economic policy management.

The impact of global trade realignments on the Australian dollar will depend on multiple factors, including how effectively Australia strengthens its trade relationships, the long-term effects of US economic policies, and the overall confidence in global markets. If Australia successfully positions itself as a key player in Asia-Pacific trade, supported by strong commodity demand and a stable investment environment, the likelihood of a stronger Australian dollar increases. However, the government and businesses must closely monitor exchange rate movements to ensure that export competitiveness is not compromised.

A shift in currency strength is just one of many potential economic outcomes from a changing global trade landscape. While a stronger Australian dollar may offer benefits in purchasing power and investment attractiveness, maintaining a well-balanced economy will be essential to ensure that Australian exporters remain competitive and that economic growth remains sustainable in the long term.

A Future Built on Strength, Not Dependence

The global economy is in a state of transformation, and the potential isolation of the United States from major trade agreements presents challenges and opportunities for nations like Australia. While initial disruptions may create uncertainty, history has shown that economies that adapt and diversify emerge stronger, more resilient, and better positioned for long-term success. Rather than relying on traditional trading partners or outdated economic structures, Australia has the chance to embrace a future built on strategic independence, innovation, and strengthened global alliances.

A shift from reliance on US trade will require businesses to rethink their supply chains, seek competitive alternatives, and invest in relationships with emerging markets. The increasing prominence of Asia-Pacific economies, combined with Australia’s strong position in regional trade agreements such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), provides a foundation for securing stable and diversified trade partnerships. By capitalising on these agreements, Australia can mitigate risks associated with economic volatility in the US while enhancing its role as a key trading hub in the Asia-Pacific.

Expanding domestic manufacturing is another crucial step towards long-term economic resilience. A stronger industrial base, supported by advanced manufacturing techniques, renewable energy production, and technological innovation, will reduce dependence on foreign imports and create high-value industries within Australia. Government incentives, investment in research and development, and workforce upskilling will ensure Australian businesses can compete in an increasingly competitive global market.

The potential for a stronger Australian dollar also presents opportunities and challenges. While an appreciating currency can increase purchasing power and attract foreign investment, careful economic management will ensure Australian exporters remain competitive. A well-balanced trade strategy, focused on strengthening domestic industries and expanding international market access, will maintain economic stability.

Supply chain resilience will be one of the defining factors in shaping Australia’s economic future. The disruptions of recent years, from the US-China trade war to pandemic-induced shortages, have demonstrated the risks of over-reliance on any single market. Businesses that take proactive steps to diversify their sourcing strategies, invest in alternative suppliers, and leverage digital technologies for logistics and procurement will be better equipped to navigate future economic shifts.

This period of global realignment is not simply a challenge to be managed—it is an opportunity to redefine economic priorities, strengthen industries, and create a future that is not dependent on any single economic power. The United States policies will not determine Australia’s economic success but the ability of businesses and policymakers to adapt, innovate, and forge new trade relationships.

As industries reassess their strategies and seek new growth avenues, now is the time for Australian businesses to position themselves for long-term success. Understanding the evolving global landscape, evaluating supply chain vulnerabilities, and exploring new market opportunities will be key to staying competitive.

SBAAS provides expert guidance to help businesses navigate these complexities, offering tailored strategies for risk management, market expansion, and operational resilience. To explore how your business can thrive in a changing global economy, contact SBAAS today. Learn more and book a consultation.

Eric Allgood

Eric Allgood is the Managing Director of SBAAS and brings over two decades of experience in corporate guidance, with a focus on governance and risk, crisis management, industrial relations, and sustainability.

He founded SBAAS in 2019 to extend his corporate strategies to small businesses, quickly becoming a vital support. His background in IR, governance and risk management, combined with his crisis management skills, has enabled businesses to navigate challenges effectively.

Eric’s commitment to sustainability shapes his approach to fostering inclusive and ethical practices within organisations. His strategic acumen and dedication to sustainable growth have positioned SBAAS as a leader in supporting small businesses through integrity and resilience.

Qualifications:

- Master of Business Law

- MBA (USA)

- Graduate Certificate of Business Administration

- Graduate Certificate of Training and Development

- Diploma of Psychology (University of Warwickshire)

- Bachelor of Applied Management

Memberships:

- Small Business Association of Australia –

International Think Tank Member and Sponsor - Australian Institute of Company Directors – MAICD

- Institute of Community Directors Australia – ICDA

- Australian Human Resource Institute – CAHRI

-

Business in the Wonderful World of Oz – Workplace Health and Safety – A Comprehensive Guide

$29.95 Add to cart -

Business in the Wonderful World of Oz – Risk Management – A Comprehensive Guide

$29.95 Add to cart -

Business in the Wonderful World of Oz – Property Leasing – A Comprehensive Guide

$29.95 Add to cart -

Business in the Wonderful World of Oz – Intellectual Property Rights – A Comprehensive Guide

$29.95 Add to cart -

Business in the Wonderful World of Oz – Future-Ready: Navigating Change and Seizing Opportunity in Australian Business

$29.95 Add to cart -

Business in the Wonderful World of Oz – Fair Work – A Comprehensive Guide

$29.95 Add to cart -

Business in the Wonderful World of Oz – Export and Global Trade – A Comprehensive Guide

$29.95 Add to cart -

Business in the Wonderful World of Oz – Cyber Security – A Comprehensive Guide

$29.95 Add to cart -

Business in the Wonderful Land of Oz – Australian Consumer Law – A Comprehensive Guide

$29.95 Add to cart -

Business in the Wonderful World of Oz – Crisis Management

$29.95 Add to cart -

Business in the Wonderful World of Oz – The Ultimate Guide

$29.95 Add to cart